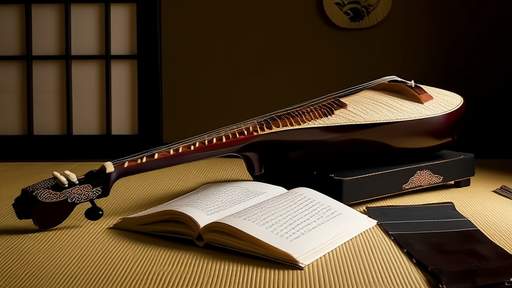

The haunting twang of the shamisen has echoed through Japanese culture for centuries, its distinctive sound inseparable from the traditional cat skin stretched across its resonating body. For generations, craftsmen have relied on salt curing – an ancient preservation method – to prepare these feline pelts. But in contemporary workshops from Tokyo to Kyoto, a quiet revolution is unfolding as modern alternatives challenge this centuries-old practice.

Walking into the humid backroom of a traditional instrument workshop in Osaka, the sharp mineral scent of salt used to dominate the air. Master craftsmen would spend weeks pressing, turning, and monitoring cat skins submerged in coarse salt crystals. The process drew moisture from the pelts while preventing decay, creating the ideal taut membrane for shamisen construction. Yet this method, while effective, presented challenges that modern artisans could no longer ignore.

The ethical concerns surrounding cat skin sourcing have intensified in recent decades. While traditional salt curing doesn't require fresh pelts, the very act of obtaining cat skins has drawn increasing criticism from animal welfare groups. This scrutiny has forced the shamisen industry to confront uncomfortable questions about material sourcing, even as practitioners defend the cultural significance of their craft. The tension between preservation and progress hangs heavy in workshop air thick with wood shavings and lacquer fumes.

Scientific advancements have yielded surprising alternatives. Researchers at Kyoto University developed a synthetic membrane that mimics the acoustic properties of cured cat skin with remarkable precision. Made from advanced polymer composites, these artificial materials eliminate ethical concerns while providing consistent quality – a crucial factor for professional musicians. Early adopters report that instruments fitted with these modern membranes retain the shamisen's characteristic "neko no koe" (cat's voice) timbre, that plaintive cry which has defined Japanese folk music for generations.

Traditionalists argue that no synthetic material can replicate the subtle variations inherent in natural skins. They point to how aged cat leather develops unique playing characteristics over years of use, becoming softer and more responsive to the bachi plectrum's strikes. Yet even among conservative craftsmen, some have begun experimenting with hybrid approaches – using minimal salt curing in combination with modern tanning agents to reduce processing time while maintaining acoustic quality.

The environmental impact of traditional salt curing has also come under examination. Large-scale salt processing requires significant water resources and produces concentrated brine runoff that can damage local ecosystems. Modern tanning alternatives, particularly those using plant-based compounds, offer more sustainable solutions without compromising the instrument's structural integrity. Several forward-thinking workshops now advertise "eco-shamisen" lines featuring these innovative materials.

Musicians find themselves at the heart of this transition. While some veteran players cling stubbornly to their cat skin instruments, younger performers often embrace the consistency of synthetic heads. Recording artists particularly appreciate how artificial membranes remain stable under studio lights and humidity fluctuations. The Tokyo National University of Fine Arts recently conducted blind listening tests, revealing that even seasoned shamisen instructors struggled to consistently identify instruments using modern materials.

Economic factors further complicate the picture. Genuine salt-cured cat skins have become prohibitively expensive due to shrinking supply chains and increased regulation. A single high-quality pelt can cost more than the wooden body of the instrument itself. This financial pressure accelerates adoption of alternatives, particularly among student musicians and regional theaters operating on tight budgets. The market shift has prompted even century-old manufacturers to diversify their product lines.

Cultural preservationists watch these developments with cautious optimism. While committed to safeguarding traditional techniques, many recognize that adaptation ensures the shamisen's survival in modern Japan. Museums now carefully document the salt curing process through video archives and live demonstrations, even as contemporary workshops transition to newer methods. This dual approach maintains knowledge of historical practices while allowing the living art form to evolve.

The quiet drama unfolding in shamisen workshops reflects broader tensions between heritage and innovation. As craftsmen weigh tradition against progress, their decisions will shape the instrument's future sound. Whether through advanced polymers or modified curing techniques, the quest continues to capture that perfect, plaintive tone – the soulful wail that has defined Japanese musical storytelling since the Edo period. The shamisen's voice may change its timbre, but its cultural resonance endures.

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025