The Faroe Islands, a remote archipelago in the North Atlantic, are known for their dramatic landscapes, rugged coastlines, and a cultural heritage that has remained largely untouched by the rapid modernization of the mainland. Among the many traditions that have survived in this isolated corner of the world, the art of playing the fiddle—or "Faroese fiddle"—stands out as a testament to the resilience and creativity of its people. The instrument, often strung with sheep gut, carries with it the echoes of centuries-old melodies, each note a whisper of the past.

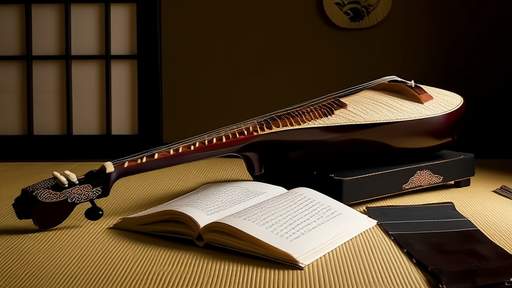

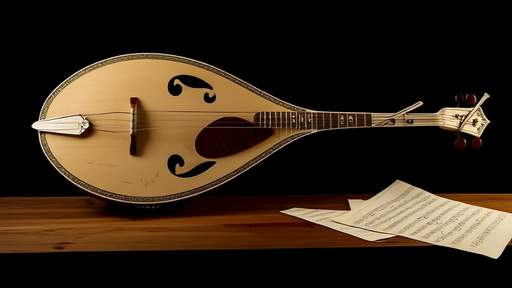

The fiddle has long been a cornerstone of Faroese music, though its origins are shrouded in mystery. Unlike the violins of classical Europe, the Faroese fiddle is a simpler, more rustic instrument, often handmade by local craftsmen. Its sound is raw and haunting, perfectly suited to the windswept cliffs and fog-draped valleys of the islands. The use of sheep gut for strings, a practice that dates back to medieval times, adds a distinctive texture to the music—a sound that is at once fragile and powerful.

For generations, the fiddle has been more than just an instrument; it is a vessel for storytelling. The Faroese have no written literary tradition until relatively recently, so their history, myths, and legends were passed down orally—often through song. The fiddle’s melodies serve as a bridge between the past and present, carrying tales of sea voyages, love lost, and battles fought. In a land where the sea is both provider and taker, the music reflects the duality of life on the edge of the world.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the Faroese fiddle tradition is its improvisational nature. Unlike the rigid structures of classical music, Faroese fiddlers often play by ear, weaving variations into familiar tunes. This fluidity allows for a deeply personal expression, where no two performances are ever quite the same. The music is alive, evolving with each player’s touch, much like the ever-changing weather of the North Atlantic.

Despite its cultural significance, the Faroese fiddle has faced challenges in the modern era. The advent of radio, television, and digital music has diluted many traditional practices, and younger generations are increasingly drawn to global sounds. Yet, there remains a dedicated group of musicians and enthusiasts working to preserve the craft. Workshops, festivals, and informal gatherings keep the tradition alive, ensuring that the fiddle’s voice does not fade into silence.

The sheep gut strings, in particular, are a symbol of this enduring connection to the land. Faroese sheep, a hardy breed that has roamed the islands for over a thousand years, provide not only wool and meat but also the materials for music. The process of crafting gut strings is labor-intensive, requiring skill and patience, but the result is a sound that cannot be replicated by synthetic alternatives. It is a sound that carries the essence of the Faroe Islands—a whisper of wind, the cry of seabirds, the pulse of the ocean.

Today, the Faroese fiddle is experiencing something of a revival. Musicians are blending traditional tunes with contemporary influences, creating a new genre that honors the past while embracing the future. This fusion has attracted attention beyond the islands, introducing global audiences to a music that was once heard only in remote villages. Yet, even as the fiddle finds new listeners, its soul remains rooted in the wild, untamed beauty of the Faroe Islands.

To hear the Faroese fiddle is to hear the heartbeat of the North Atlantic. Its melodies are a reminder of a time when music was not just entertainment but a lifeline—a way to make sense of the world. In the hands of a skilled player, the fiddle becomes more than an instrument; it is a voice, a storyteller, a keeper of memories. And as long as there are those who listen, the music of the Faroe Islands will continue to resonate across the waves.

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025