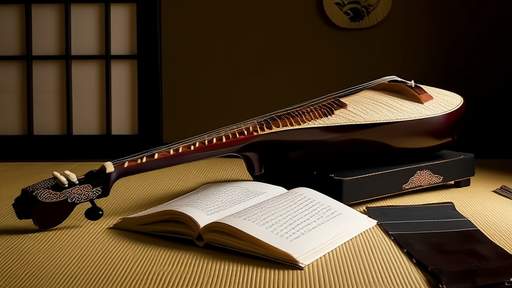

The Appalachian dulcimer, with its haunting melodies and distinctive shape, stands as a testament to the cultural alchemy of early Scottish immigrants in America’s mountainous regions. This humble instrument, often overlooked in broader discussions of folk music, carries within its strings a story of adaptation, survival, and the quiet resilience of a people far from home. Its evolution from European predecessors to a uniquely American artifact reveals how isolation and necessity can birth artistic innovation.

When Scottish settlers arrived in the Appalachian Mountains during the 18th and early 19th centuries, they brought with them the musical traditions of their homeland. Among these was the zither, a flat-bodied string instrument common in Germanic and Celtic cultures. But the rugged terrain and scarce resources of Appalachia demanded reinvention. Luthiers, often working with nothing more than hand tools and local timber, began reshaping the zither into something new. The result was the Appalachian dulcimer—a narrower, elongated instrument with fewer strings, designed to be played on the lap rather than a table. Its pared-down construction reflected both the scarcity of materials and the practical needs of mountain life.

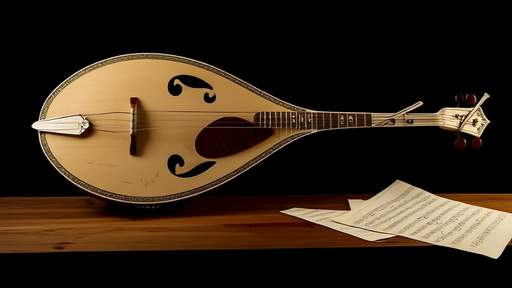

The dulcimer’s sound became the voice of Appalachia itself—mournful yet hopeful, simple but layered with meaning. Unlike the bagpipes or fiddles of Scotland, which demanded robust technique, the dulcimer could be mastered with relative ease. This accessibility made it a favorite among settlers who lacked formal musical training but yearned to preserve their heritage. Women, in particular, took to the instrument; its soft tones suited the intimate gatherings of frontier homes. Over time, the dulcimer absorbed influences from English ballads, African rhythms, and even Native American melodies, becoming a sonic tapestry of the region’s diverse roots.

What’s most striking about the Appalachian dulcimer is how it embodies the Scottish immigrant’s relationship with the land. The mountains, though foreign at first, became a crucible for cultural transformation. The instrument’s wood—often carved from local spruce or walnut—literally rooted it in Appalachian soil. Its melodies, while echoing old Scottish airs, gradually incorporated the cadences of winding rivers and bird calls unique to the New World. This wasn’t mere preservation; it was a dialogue between memory and environment, a musical response to the question of how to belong in an unfamiliar place.

By the early 20th century, the dulcimer had faded into obscurity, nearly vanishing as industrialization drew people away from mountain life. Its revival in the 1950s and 60s, led by folk enthusiasts like Jean Ritchie, reintroduced America to this forgotten artifact. Today, the instrument enjoys a quiet renaissance, cherished by musicians who value its history as much as its sound. In its strings, we hear not just notes, but the story of Scottish immigrants who—through wood and wire—found a way to make the Appalachian highlands feel like home.

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025