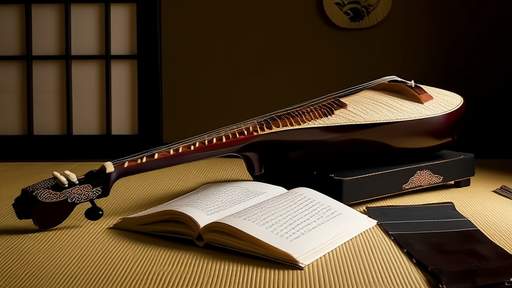

The tzouras, a long-necked lute deeply rooted in Cypriot musical tradition, embodies the cultural crossroads of the Mediterranean. Unlike its more famous cousin, the bouzouki, the tzouras carries a distinct tonal character and playing style that reflects the island’s layered history. Its hybrid tuning systems—often blending Byzantine, Ottoman, and Greek influences—speak to centuries of exchange and adaptation. To understand the tzouras is to glimpse the sonic tapestry of Cyprus itself, where melodies weave together the legacies of empires, migrations, and resilient local identity.

What sets the tzouras apart is its improvisational flexibility. Players frequently adjust tunings to suit specific dromoi (musical modes) or regional repertoires, creating a fluid interplay between structure and spontaneity. In coastal towns like Larnaca, the instrument might be tuned to accommodate karsilamas rhythms, while in the Troodos Mountains, darker, microtonal scales echo Byzantine chant. This adaptability has allowed the tzouras to thrive in both rebetiko ensembles and village folk celebrations, bridging urban and rural soundscapes.

The construction of the tzouras reveals its hybrid nature. Its body, often carved from mulberry or walnut, is shallower than a bouzouki’s, producing a sharper, more intimate tone. The neck—sometimes extending over 80 cm—allows for wide intervallic leaps, demanding a technical prowess distinct from other lute-family instruments. Older models feature movable frets made of tied nylon, enabling minute pitch adjustments for maqam-like ornamentation. Modern luthiers, however, increasingly use fixed frets to accommodate Westernized scales, sparking debates about authenticity among traditionalists.

Historically, the tzouras served as both solo and ensemble instrument. During Ottoman rule, it accompanied divan poetry recitations in coffeehouses, its metallic teli (brass strings) cutting through the murmur of patrons. Post-1930s, Cypriot migrants brought it to Piraeus, where it absorbed elements of the urban rebetiko sound. Yet unlike the bouzouki’s global fame, the tzouras remained a cult instrument, its nuances guarded by village masters. Recent revival efforts, led by musicians like Michalis Tterlikkas, emphasize its role in pentozalia dances and lamentatory mirologia, reconnecting younger generations to this sonic heritage.

The island’s political divisions have also shaped the tzouras’ evolution. In northern Cyprus, Turkish-Cypriot players often incorporate saz techniques, blending Kurdish dengbêj vocal styles with Greek melodic forms. Meanwhile, southern players increasingly experiment with cross-cultural collaborations, such as fusing tzouras with Armenian duduk or Lebanese oud. These innovations highlight the instrument’s role as a mediator—its strings resonating with both partition and unity.

To hear the tzouras today is to witness a living archive. From the wine-dark drones of a tsifteteli rhythm to the intricate taximia (preludes) that mimic the calls of migratory birds, its voice carries the weight of an island that has always been a melting pot. As Cypriot musicians navigate globalization, the tzouras remains a testament to resilience—an instrument that refuses to be standardized, its tunings as fluid as the sea surrounding its homeland.

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025