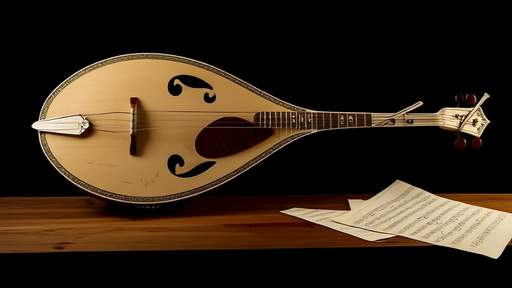

The haunting twang of the bouzouki has long been the soundtrack to Greece’s winding backstreets and moonlit tavernas. Yet few instruments have undergone as radical a transformation as this iconic lute, particularly through the hands of the peripatetic musicians who shaped its modern voice. The 20-fret bouzouki revolution—spearheaded by itinerant players in the mid-20th century—didn’t just alter an instrument; it rewrote the DNA of Greek music itself.

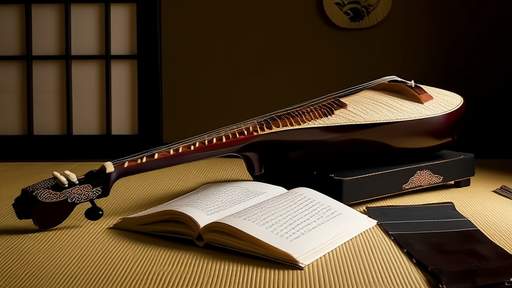

Originally a three-course (six-string) instrument with limited range, the bouzouki was the weapon of choice for rebetiko musicians—Greece’s underground bluesmen who sang of hashish dens and heartache. Its metallic resonance cut through the smokey air of tekédes (hash dens), where players like Markos Vamvakaris forged raw urban poetry. But as rebetiko crawled from the margins into mainstream acceptance after WWII, the bouzouki’s limitations became apparent. Four-course versions (eight strings) had existed since the 1920s, but it took the restless innovation of traveling virtuosos to unlock its potential.

The pivotal shift came with the addition of four extra frets—expanding from 16 to 20—a modification credited largely to Manolis Chiotis, a prodigy who treated the bouzouki like a flamenco guitarist’s weapon. This wasn’t mere tinkering; it was alchemy. The extended fretboard allowed chromatic runs previously impossible, bending microtones into submission while opening doors to jazz and Western harmonies. Suddenly, the bouzouki could duel with violins in dimotika (folk dances) or weave through complex zeibekiko rhythms with razor precision.

What’s often overlooked is how migrant musicians became the revolution’s foot soldiers. As Greece urbanized, players from Asia Minor and the islands brought regional tunings into collision. A Cretan lyra player might retune the bouzouki’s trichordo (D-A-D) to match his own scales, while Smyrnaic refugees doubled melodies with oud-like flourishes. These sonic nomads—often playing for coins in Piraeus dockside bars—turned the instrument into a hybrid beast, its 20 frets absorbing everything from Byzantine echoi to Turkish makams.

The technical leap had cultural ramifications. When Vassilis Tsitsanis composed his seminal rebetika on a 20-fret bouzouki, he bridged old and new Greece—the amané wail of the past meeting cosmopolitan swing. Meanwhile, players like Yiannis Papaioannou exploited the extended range to compose intricate taximia (improvisations), transforming what was once accompaniment into a lead instrument capable of breathtaking solos. By the 1960s, the bouzouki’s metallic cry was no longer confined to the underworld; it scored films, entranced aristocrats, and even infiltrated the pop charts.

Yet for all its sophistication, the 20-fret revolution never fully severed the bouzouki’s ties to its rogue origins. Listen closely to a Chiotis tsiftetéli, and beneath the pyrotechnics you’ll still hear the ghostly echo of prison songs and outlaw laments. That duality—technical prowess rooted in raw emotion—may be the greatest legacy of those wandering players who turned a humble lute into Greece’s musical soul.

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025